Related content

-

UK hospitals use metal Additive Manufacturing to save patient limbs

The trauma and orthopaedic team at St George’s Hospital, Stafford, UK, recently implanted a metal additively manufactured bone cage in order to save a patient’s limb after he had sustained an open fracture to his right tibia and fibula (the two bones that make up the lower leg).

Over the past few years, 3D-printing technology has been increasingly applied to the production of advanced engineering components for sensors. Advances in the technology, which uses melting and solidification processes to fabricate devices with flawless surface finishing and highly accurate dimensions, have reduced power and material consumption and complex parts can now be synthesized in hours rather than weeks.

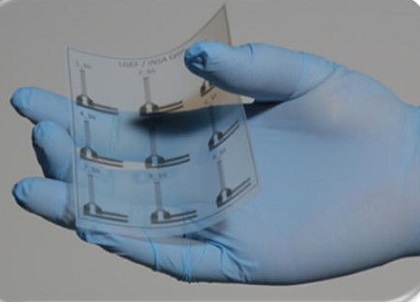

Examples of 3D-printed sensors

Sensors can detect and convert many physical quantities into electrical signals and 3D-printed sensors are now commonly used in consumer goods. Depending upon the physical quantity, various sensors have been fabricated using 3D printing, including devices with high resolution to detect force, acceleration, displacement, strain, pressure and temperature. Indeed, 3D printing has offered new sensor concepts that can be used on garments and textiles. Following are details about each type of sensor.

Force sensors convert the applied forces to electrical signals and are usually made up of packaging, a flexure and a transducer. 3D-printing technology can cheaply fabricate all of these main parts and offers customization. Moreover, 3D-printed transducers are also compatible with a wide variety of flexure displacements and dimensions. For printing accelerometer sensors, polyethylene terephthalate material as a printing base has proved to be most flexible and polyvinyl alcohol and silver paste have been utilized as sacrificial and structural materials. For removing the sacrificial layer without destroying the structural layer, a solvent that does not affect or contact the silver layer is applied.

Strain sensors are manufactured from a mixture of the flexible conducting substrate, integrated or glued to a stretchable substrate. Soft matrices are used to produce different personalized shapes of extendible and conformal 3D-printed strain sensors, and materials such as graphene, nanotubes and nanoparticles have been used for constructing printing inks. The finite difference method is being used for printing to quantify a given pressure and adjust geometrical features in printed components. This method has enabled development of devices with fiber Bragg grating sensors integrated into the printed portion.

This technology is also being extensively used for manufacturing both flexible and rigid temperature sensors. 3D inkjet printers available to synthesize temperature sensors feature 8 m/s velocity of the drop and 40◦ C printhead temperature, enabling printing of requisite silver structures. Tactile, particle and biomedical sensors are also being produced with 3D-printing technology.

Despite these advances, challenges remain to the continued evolution of 3D-printing technology for sensors.

Challenges of 3D-printing technology

There is still room for improvement in the additive manufacture and performance of 3D-printed sensors and will require expertise in electronics, mechanics and materials science. The biocompatibility of materials must be considered along with biomimetic design and nanomotor properties.

In this fast 3D-printing process, limitations imposed by a material is a major challenge as they can affect the reliability and performance of sensors. The use of nanoparticles for printed sensors poses another challenge, as their tiny size makes it possible for them to cross cell membranes. Therefore, in medical applications, health and safety problems can be a major concern for nanoparticle-based printed medical sensors.

An additional obstacle to the development of 3D-printed sensors is the lifetime of the engineered parts. These sensors are still under development, and thus there is not much knowledge about longevity and contributions of this technology to the expanding volumes of electronic waste worldwide.

Conclusion

Undoubtedly, the advancements in 3D-printing technology have made it possible to fabricate cheap, sensitive, flexible and miniaturized sensors for use in diverse engineering and medical disciplines. This promising technology does come with major challenges that must be dealt with by experts from the fields of electronics, mechanics and materials sciences. Fortunately, new additive manufacturing platforms and related software are being developed to improve consistency by preventing or correcting common errors or mistakes, including the use of inadequate print files, unlevel build plates and the inappropriate selection of nozzles for the desired output.

https://electronics360.globalspec.com

沪公网安备31011802004991

沪公网安备31011802004991